By: Iván Diego/Asturias4Steam.

By way of scene-setting, would you like to introduce yourself?

I originally trained as a Physicist in my undergrad and for a time I envisioned going on to become an academic physicist. I became far more interested in researching physics education and started my career as a physics teacher in Toronto. It was there, in my early years of teaching school, where I first developed this interest in the intersections between science, technology and making. I realised that maybe the ideas about connections between science, technology, and art that I took for granted were not neccesarily shared by my students, even those that wanted to go into engineering.

So what was the situation back then?

At the time there was a shutting down of many technology courses in Canada. That was very problematic for students who said they wanted to be engineers but never touched mechanical things with their hands before entering university.

Is STEM education popular in Canada?

Like in many other places, STEM is quite popular. Education in Canada is provincially mandated so the science (and indeed any subject) curricula changes depending on the province. There’s a general enthusiasm for STEM among Science teachers and Primary teachers in particular, partly because our neighbours to the south put a lot of political effort and money into high-profile people advocating for STEM. So while there’s coherent enthusiasm I would say there’s less coherent adoption of what it actually means in practice. Some teachers have adopted it quite strongly as a part of their identity, they call themselves STEM teachers, whilst there are some people who would frankly say that STEM is just a repackaging of old things.

Are these four letters equally represented in the acronym?

It’s not terribly funny but there’s a joke I often use. Think about STEM as a sandwich with the S as the top slice of bread and the M as the bottom slice of bread. The bulk of the sandwich, the Technology and Engineering parts are actually quite thin in comparison to the thickness of the slices of bread.

The situation here is somewhat different. On the one hand STEM tends to be equated with Technology and on the other engineering is sort of engulfed or swallowed by Technology. Engineering is playing second fidde to technology.

I would agree with you that the gateway or the thing that labels it as a STEM activity is the Technology bit–robotics lessons, for instance.

Let’s talk about your research. What prompted you to choose Maker Pedagogy as a research topic?

I’m a bit of a curricular pessimist and that’s really the crux of why I started it and why I walked away from it for a while. When I first heard about the Maker Movement I was reminded that in the late 50ies we started this political discourse around science literacy, which was framed as a way of keeping up with the Soviet Union. Twenty years later science literacy came to mean everything to do with science education. We then we moved on to scientific literacy debates and then on to STEM. My concern was that Making was an attempt to rebrand some of the ideas that we talked about in science and technology education for a long time—many of which started as policy debates rather than being informed by research.

At some stage it seemed like Making became the cool thing to do

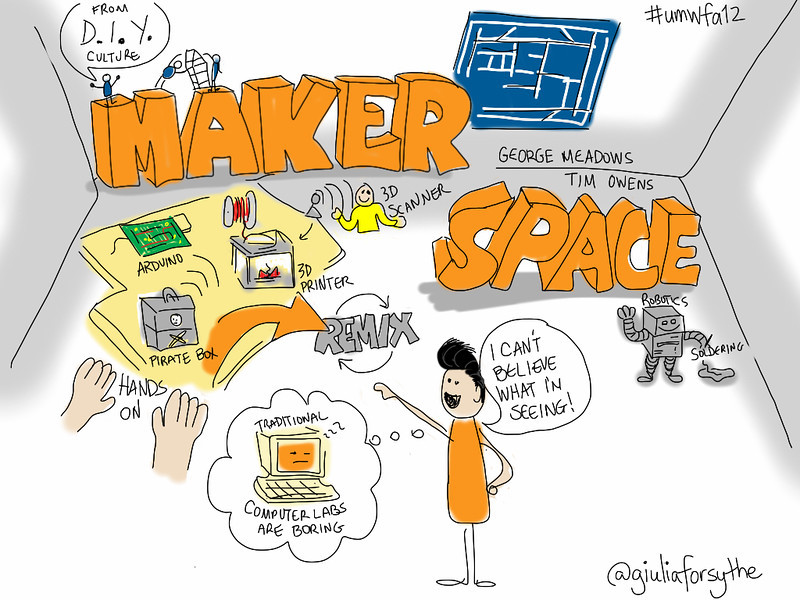

Precisely. It was hard to deny that there was a certain element in the zeitgeist that was very interested in making things. When I was a secondary school teacher I noticed how few opportunities many students seemed to have to actually “make a thing” beyond the early grades of school. So I thought, is there actually something there? How might we separate upper case Maker Movement, the commercialised, “Buy-This-Kit” comercial enterprise and the lower case maker movement, which might be more about collective endeavours to share tools, knowledge, and build community?

So how would you define Maker Pedagogy?

Thinking about ideas around design, adapt, create and ethically hack was my starting point. And I’m very clear in saying that in fact nowadays I think those terms are limited, but they were a starting point for me to work with elementary school teachers and say, “Ok, here are the starting principles and here are the activities we’re going to use to think about them” whilst all the while being mindful of what sociologist Neil Selwyn calls the tendency toward presentism in edtech research. Selwyn also reminds us of the importance of asking “What’s new here?” and making sure there is nothing to “sell” in EdTech research. I spent a productive 3 years but then I needed to take a break from it.

Physicality, participatory action seems implicit in Maker Pedagogy but authors like Jonathan Osborne suggest hands-on learning may not suffice if not accompanied by minds-on learning. So the question is not learning by making but by making what and more importantly why.

Absolutely. I worked with elementary teacher candidates to help them to explore the principles of the maker movement without being initially constrained by the idea that it has to be something that’s physical or “hands-on.” But at the same time I was aware that many elementary school teachers, particularly if they don´t have a Science background, express discomfort in some of the materialaspects of science and technology education. So initially I wanted to help them to develop a bit more confidence.

What was the most unexpected outcome of your research?

One of the big findings of my 3-year research is what started as a way to engage elementary teachers candidates in thinking about Making within their own practice actually turned out to be more about the conversations the teacher candidates had as a community around the act of making whatever it is they were making. So although I may have been interested in them learning a bit of Electronics, that interest very much took a back seat to the kinds of conversations about professional knowledge that techer candidates had when they were having this collective experience of making. And for me that result, the emphasis on the importance of dialogue, was quite shocking and powerful and that’s what really made me want to take a step back and really think what this research might be.

More and more schools setting up FabLabs but sometimes you just get the impression that’s what it’s all about. There’s the irresistible allure of technology and in some case, all this (EdTech)Arms Race is used as a marketing tool to stand apart from other schools but the political/ethical implications of the Maker Movement evaporate into thin air. How do you stop this from happening?

The idea of competition and a focus on “acquisition of technology” was something I was really conscious of as well. One of the things I decided at the beginning was to explicitly use materials and software that were free or readily accesible to many people. For example, we used very very simple physical equipment so if candidate teachers were to go home and replicate what they did it would cost them around 10€ in materials. Some projects could be completed without spending any money. My rule was “Nothing expensive and nothing in pre-fabricated kits.” I think that decision helped me to avoid the more commercial elements of capital-M making.

We have a journal club with science & technology teachers and there was this discussion between elitist approaches to technology vs more inclusive approaches. Some schools in socially-disadvantaged areas frame it in a more inclusive way, they see their makerspaces as ways to grant access to these technologies to kids that otherwise won´t have the chance to interact with.

One thing I’m really concerned about is Making and Maker approaches reinforcing existing class divides in society, where “making things” becomes the domain of people who have a certain amount of money to buy certain things and to use them in a large space.

Schools in general have been framed, generally, as a way of trying to ensure a more equitable land of opportunity for students and I think that’s a laudable goal–but simply giving schools equipment will not necessarily yield the desired outcomes. I certainly support schools using everything they have be it through donation, benefactor, or purchases from departmental funding. That’s all really helpful but what I want to avoid though in my own reseach is making participants feel like they have to purchase certain things. So if teachers and students so happen to have access to FabLabs, 3Dprinters, arduino controllers, and the like, then that’s great. But you can learn just as much from other, more readily available materials and processes. I felt strongly about the issue of not having a barrier for those who want to think about making and maker pedagogy. I do not want access to certain technologies to function as a gatekeeper.

You had some intial principles but you said you have changed your mind

One of my Master’s students was a experienced STEM teacher who adopted a Making approach within a specialized course. One of the things she reported was the issues of identity that were raised for her as a result of trying to frame herself within a Making/Technology role as opposed to her previous teaching roles. That result provided one clue for me. But it was through our work with candidate teachers that I started to see that perhaps what I thought were not hard lines but more easily divisible factions around my initial conceptualisations of design/create/adapt/ethically hack. The first three have now become subsumed under the ethical hacking.

What do you exactly mean by hacking?

In his book Permanent Record (2019) Edward Snowden talks about his journey learning about computers and offers an interesting definition of hacking. It’s about knowing something as well as you can possibly know it. It’s about knowing the rules for a particular system or device and understanding the full suite of possibilities. It’s about taking whatever issue you’re interested in, approaching it from as many angles as possible, constructing it, reconstructing it, and making mistakes. And that gave me the metaphor for thinking about where I might like to take Maker Pedagogy.

So what are the implications of embracing this hacking perspective for teaching & learning?

If we think about what it means to hack something, to really understand how you’re using whatever material you have in front of you, then I believe that the learner is liked to get a different kind of mastery over their own context and their particular situation and that would be a more helpful way of thinking about what might be different about making within the genres of Science, STEM and so on.

In your article you mention Making as a metaphorical compass for Curricular Making. It’s quite a big conceptual leap, isn´t it? How can you possibly hack a curriculum?

It’s not an easy process to make that metaphorical leap. Another big field of what I do is called self-study research of teaching and teaching education practices. It’s similiar to action research in the sense that you do something in your classroom and you analyse what happens. Unlike action research, though the focus of the data analysis isn´t on students results but on teachers. Self-study challenges teachers and education academics to respond to the question: “How do I understand my teaching differently as a result of enacting a particular practice?” If you’re thinking about yourself as a Maker in your teaching, I would encourage you to think about how your identity as a maker interacts with the students and colleagues you’re working with, the material and non-material aspects of your classroom, and the oficial and non-official curricula with which you work. Doingso requires a continuous rigorous examination of your own practices, the reasons underpinning them and the enabling constraints in your own teaching environment.

Teachers seeem to be under a lot of pressure to keep up with all the new (and supposedly ground-breaking, game-changing) educational technologies and gadgets.

I worry about that a lot, particularly if teachers feel: “This week I have to learn about Arduino and then in a few weeks they’re expected to do a MakeyMakey kit.” I’d really like to invite teachers to think about one thing they would like to take on, if they are interested in maker pedagogy. I would hope that they would have appropriate supports so that they might take an long time to develop mastery rather than worrying about trying to catch up with everything that’s been thrown at them.

“Learning by failure”, ”Fail fast, Fail forward” and mantras of its ilk pervade educational rethoric but at the end of the day failure has got a bad reputation in Education.

Kevin O’Neill (2012) (see “Designs that fly: what the history of aeronautics tells us about the future of design-based research in education”, in the International Journal of Research and Method in Education) wrote about the importance of reporting failures in EdTech research, and design-based research in educaiton more generally. I think there’s a pressure for reasearchers and teachers alike to prove that something has really “worked” – otherwise there is a fear that it won´t get published. But that’s not all that helpful. It’s much more productive to talk about the messiness of practice and research – I think that’s crucial.

Are you planning to resume your research in Maker Pedagogy?

I really want to pursue this idea of Hacking as the fundamental point of departure rather than looking at particular projects in support of Maker principles. Frankly I can take any experiment or demonstration and turned into a capital M Maker project but that would be too simplistic a switch. What I would rather ask is: “How might I work with teachers to find opportunities for students to hack something; that is, to develop a really sophisticated knowledge of how a particular process, experiment or device works?” What might that mean for the quality of student’s learning, not just in “science class”, but in any subject across the curriculum? What does it mean to “hack” in a given discipline taught in school?

And finally, an article you’d reccomend?

Neil Selwyn’s article “In Praise of Pessimism – The need for negativity in Educational Technology” has been a really useful way of always trying to have a critical lens and tempering my natural DIY/Tech enthusiasm. And I recommend Kevin O’Neill’s article “Designs that fly: what the history of aeronautics tells us about the future of design-based research in education”, for reasons cited above.

I have really enjoyed this conversation that opens up lots of interesting areas to explore. Thanks for your time. Let’s stay in touch.

To learn more